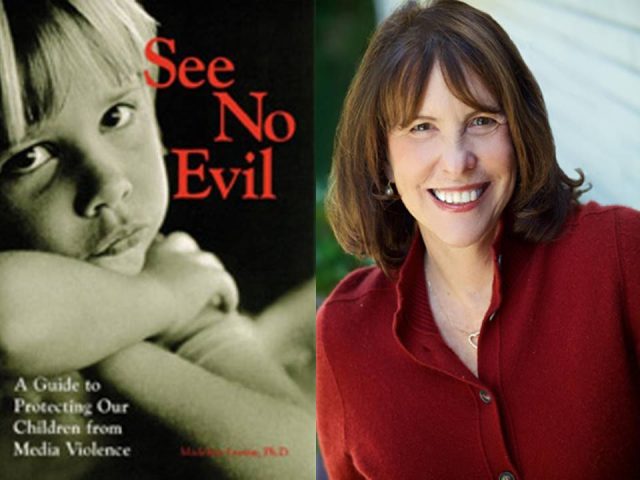

On September 11, 1998, Madeline Levine’s book See No Evil, a revised and updated version of her classic book Viewing Violence, was published. Madeline Levine, Ph.D. is a psychologist who has almost 40 years of experience as a clinician, consultant, and lecturer. She specializes parenting issues and was an instructor in child development at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center. She is a popular speaker on the topics of media violence and child development. In See No Evil, Levine presents evidence that “media violence encourages aggression, desensitization, and pessimism in children”. Here she shows how violence from the media influences the different stages of child’s development while also presenting practical solutions for parents who want to do something about it.

Examining the media from the point of view of the children at different stages of development, Levine explores the impacts of television and movie programs to their psychology, behaviours, actions, their emotional aspect, and to how they socialize in general. And to offer options for parents, Levine provides practical guidance in choosing healthy and safe television programs and movies for children. There are also lots of checklists that can help parents have informed decisions on using the media, including recommendations for television shows and movies that are more “interesting, thoughtful, and optimistic”.

On the introduction, Madeline Levine wrote:

“The debate is over. Violence on television and in the movies is damaging to children. Forty years of research concludes that repeated exposure to high levels of media violence teaches some children and adolescents to settle interpersonal differences with violence, while teaching many more to be indifferent to this solution. Under the media tutelage, children at younger and younger ages are using violence as a first, not a last, resort to conflict. Parents, eager to protect their children from damaging influences of media, find that they are unable to find useful, accessible information about what is harmful.”

Madeline Levine also argues that results from studies on the subject of the effects of media violence to children are being kept from the public as it will negatively affect the business and hurt the media company’s profit. According to her:

“Locked away in professional journals are thousands of articles documenting the negative effects of the media, and particularly media violence, on our nation’s youth. Children who are heavy viewers of television are more aggressive, more pessimistic, less imaginative, less empathic, and less capable students than children who watch less. With an increasing sense of urgency, parents are realizing that the real story about media violence and its effects on children has been withheld.

This is not surprising. Public education often lags behind research, especially when economic stakes are high. For example, until recently, tobacco executives were still insisting that “the scientific proof isn’t in yet to link smoking and cancer.” The entertainment industry stands to lose a great deal of money if violence, a particularly cheap and reliable form of entertainment, becomes less popular.”

Madeline Levine also discussed about “copycat suicides” in the book; stating that “sensational coverage of crime and suicide by young celebrities can be emotionally devastating for vulnerable teens”. As an example, Levine used the case of Kurt Cobain, the famous musician who was a member of the very popular grunge band Nirvana. She wrote that the highly publicized “suicide” of Kurt Cobain resulted in many copycat suicides of adolescents. And to provide further example of this imitation, Levine used the story of two icons, Jacqueline Kennedy and Eddie Vedder:

“Common sense tells us that we are more likely to imitate people who are attractive, respected, and powerful. Jacqueline Kennedy’s pillbox hats and simple suits were as popular among aspiring young women in the 1960s as Eddie Vedder’s flannel shirts and ripped shorts are among adolescent suburbanites in the 1990s. Within their respective groups, these two stylish individuals – contemporary, talented, and powerful – were seen as models worthy of imitation. Imitating people who are prestigious and powerful allows us the illusion of borrowing some of their authority and privilege.”

Levine also quoted Leonard Eron, one of the Americas foremost experts on media and children, who stated:

“There can no longer be any doubt that heavy exposure to televised violence is one of the causes of aggressive behaviour, crime, and violence in society. The evidence comes from both the laboratory and real-life studies. Television violence affects youngsters of all ages, of both genders, at all socioeconomic levels and all levels of intelligence. The effect is not limited to children who are already disposed to being aggressive and is not restricted to this country.”

Meanwhile, offering a solution to parents on how to counter this culture, Madeline Levine stated:

“We need to tell our children stories that contribute to their healthy development and encourage positive behaviours rather than allowing the media to encourage negative ones.”

Reference:

See No Evil book by Madeline Levine

https://www.bookdepository.com/See-No-Evil-Madeline-Levine/9780787943479